I know him, but he doesn’t know me. We grew up at the same time and are nearly the same age. He is a star and I am a nobody. This is a very common sentence when we see all these famous people on television, in the movies or in sports competition broadcasts. But in my case it was a little bit different, more complex, tragic and maybe even a little bit touching. In our early youth Jan and I met for the first time.

I know him, but he doesn’t know me. We grew up at the same time and are nearly the same age. He is a star and I am a nobody. This is a very common sentence when we see all these famous people on television, in the movies or in sports competition broadcasts. But in my case it was a little bit different, more complex, tragic and maybe even a little bit touching. In our early youth Jan and I met for the first time.

My mother is quite scared of nearly everything. I can’t remember how often we were screamed at when we just stood kneedeep in the Baltic Sea, how often she instructed us – up until adult age – not to cross the road against the red light. And how happy she was when we lay in our beds sleeping and not having any injuries or wounds. Therefore, cycling was an extreme sport in my mother’ eyes. One of my most uncomfortable memories of my childhood is that I secretly tried to cycle when I was already 13 years old. Still I can recall the pain caused by my blue bollocks that lasted more than 2 weeks.

Approximately at the same time a young tot moved from Rostock to Berlin. He had already been very good at cycling – in contrast to me. At the age of nine he won the first race at his school and one year later an official competition having a lent bicycle and normal trainers. Soon he was said to be a real talent and the new star in cycling, leaving all his contemporaries behind. This boy’s name was Jan Ullrich.

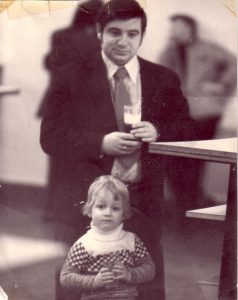

And now comes the big surprise, not only for me: my dad – as we called him at this time – had studied at the College for Physical Culture in Leipzig. He himself was quite a good javelin thrower, but that would take us too far afield. Anyway, directly after his studies he got a job at the Berlin sports club SC Dynamo, training the cyclists. Why him of all people, as he had nothing in particular to do with cycling, nobody knows. However, soon he had climbed up the career ladder, since he was quite popular not only among the cyclists, who already called him Scheppi or simply coach.

Dynamo Berlin had excellent cyclists like Carsten Wolf, Emanuel Rasch or Bill Huck, who Benny and I had already known personally, because of our dad. But the problem with them was that the best talents only did track cycling and nobody knew them, except real fans or experts. The ultimate heroes at that time were the peace cyclists, which was the counterpart of the eastern European countries to the gladiators of the Tour de France. Absolutely everybody in my class knew the complete team of the GDR – Hans-Joachim Hartnik, Bernd Drogan or Olaf Ludwig – we loved them all. However, these top athletes all were from other clubs in Leipzig, Gera or Erfurt. The big boss of the Berlin club Dynamo – Erich Mielke (also the head of the Stasi) – had been very angry about this situation. But in Rostock they had discovered a boy that was directly “delegated” to Berlin. Now they had at least one super talent for the future in the capital of the GDR – right: Jan Ullrich.

Many of our weekend trips at that time ended for my brother and me in some hicksvilles in Brandenburg where some sweating boys raced against each other on their stupid bicycles. My dad probably thought that we liked these trips – we did not! By this time I was 14 years old and I sneered at these panting idiots, who asked my father with big eyes: “Mister Scheppert, when will we get back?” Secretly I went into the cold and damp woods and smoked some Cabinet (popular East German brand of cigarettes) cigarettes while I asked myself the same question.

Also in winter the spook wasn’t over, as then the cycling races of the teens took place in the Werner-Seelenbinder-sports hall. On the breakneck circuit with the extreme inclination angle brutal croppers and severe injuries happened – on the road sometimes even a dead person. Innerly I thanked my mother whose genes were responsible for me being absolutely not sporty. When my father introduced us to the cycling boys I was grinning disdainfully. In the cafeteria I could puff a cigarette secretly.

My dad wasn’t lucky with success. The so called Olympia mission wasn’t accomplished yet again. Therefore, also in the GDR somebody had to go. Furthermore, my dad was accused to be too friendly to the young cyclist that wasn’t conducive to successful results. The first achievements of Jan Ullrich and his coach Peter Becker he didn’t experienced in a leading position anymore. Becker was said to be the hardliner among the coaches. This tough person was also the one that got me my first road bike. In case he had known that the son of his boss started cycling at the age of 13, my dad would have sacked completely at Dynamo. As fortunately nobody knew he was only redeployed to the swimming team, because of persistent unsuccessfulness.

There he was responsible to search for new talents and incredible as it sounds he recommended Franziska van Almsick to the children’s and youth sports school. I am sure that my father (not a really good swimmer) was just lucky with that decision. However, after the Wall came down in 1989 the bubble of socialist high-performance sports had been pricked. My dad whom I had always been admired – even though I didn’t like cycling – had to look for another job.

Jan Ullrich stayed with his coach Peter Becker, he became world champion of the amateurs on the road and gained a highly remunerated contract in the Team Telekom. “Ulle” – as we called him – was the second superstar of the united Germany after the swimmer “Franzi”. However, at the end of his career he was regrettably the most ham-handed and tragically fallen hero – naturally from the former GDR.

My dad got a job after quite a while of searching which was less lucrative. He worked as a caretaker in a dubious real estate agency, split up with my mother because of a younger one and from now on he stumbled from one personal catastrophe to the other until he finally lost everything, even his dignity, but that had nothing to do with the united Germany but with alcohol. When he appeared at my brother’s marriage – scruffy and drunk – I observed him with a mixture of shame and bewilderment. Being stressed out I smoked – not secretly anymore – one of my Cabinet cigarettes, the last remnant from the old days.

No! This story will and must not end so sadly.

In July 1997 my former girlfriend Danny visited me surprisingly in my student digs. Actually I must admit that we didn’t have a real relationship at that time. Intricately she explained that I had to get up very early on the next morning and pack my bags for a trip at the weekend. On the next day I found myself very early in a train to France. She had booked a weekend in Paris for us. We didn’t know each other very well, but Danny learned a lot about my past in these days.

The city was decorated with a flags, pennants and huge posters that promoted an important event on Sunday. I was excited like a small child – not because of the beautiful girl on my side, who didn’t even know that the 84th Tour de France finished exactly at this weekend. My Jan Ullrich would cycle the yellow jersey to Paris as the first German cyclist. I couldn’t talk about anything else but the small hicksville in Brandenburg called Forst where the teen races took place, about my super dad, who somehow had detected this new cycling king and even about my blue bollocks.

I was so proud and touched when the boys rolled by several times through the inner city of Paris. Tears flooded my eyes. I cheered him, this sweating boy from my childhood. How did he crucify himself in his youth without drinking binges and smoking Cabinet cigarettes. Now he rode past me with a beaming smile in his shiny yellow jersey of the winner. This moment was one of the most amazing ones in my entire life so far – for me it was like history passes by – not only the history of the two Germanys or of cycling, but also my very own. After the stage win we went to see the stars of the team Telekom. I didn’t dare to approach them instead I lit a French cigarette frantically. I knew him, but he didn’t know me.

With the help of the family, strict discipline and most of all without any alcohol my old man slowly gained control of his life step by step. He is in good health again and as a pensioner voluntarily committed in sports again. Today I am really proud of him again, when he knows nearly everybody at the Berlin six-day-race every year and also many ex-cyclists still cat-call at him: “Hey coach, you all right?” In these moments I can feel that he is happy.

And I? Well, because of both of them I became the generation Jan Ullrich. We are neither fish nor fowl, neither East nor West, not yesterday, today or tomorrow. We share the past with our parents who define themselves about their GDR and with children who don’t know this not existing country at all. We are often asked what life in this vanished country was like and when we start talking about that time nobody really listens anymore. We try to be like prosperous Wessis, but secretly we especially root for successful Ossis. We never say that in former times everything was much better, but neither we say that this is the case today. It is time to take us seriously.

.

.

Read more: Generation Wall by Mark Scheppert

.

.

.